-2.png)

DEFIANCE

DISPATCHES FROM CRIMEA

WITH LUTFIYE ZUDIYEVA

As journalists, lawyers, writers, and activists in Crimea continue to face repression and imprisonment, we share monthly updates with Lutfiye Zudiyeva.

Shedding light on the struggle for self-determination and the solidarity that endures under occupation, these dispatches offer insight into the cost of speaking out — and the courage of those who do.

Lutfiye Zudiyeva is a Crimean Tartar writer, journalist and Co-ordinator of the Crimean Solidarity human rights network.

LUTFIYE ZUDIYEVA

Lutfiye’s activism and belief in collective justice are routed in her family history and inspired by her father. She was born in Uzbekistan after her grandparents were deported by Russia alongside 190,000 Crimean Tartars in 1944. Formerly recognised as a genocide by the Ukrainian Parliament in 2015, many Crimean Tartars died during deportation and also due to the harsh living conditions in Uzbekistan. Lutfiye’s family returned to Crimea in 1989 after the collapse of the Soviet Union and Ukraine’s independence. Lutfiye was nine months pregnant with her fourth child when Russia invaded and occupied Crimea in 2014. New laws were introduced that targeted activists, journalists and lawyers. In particular they who were Crimean Tartars were singled out for expressing their language, cultural identity and advocating for their rights facing sentences of up to 15 to 20 years. As independent media was shut down, books banned and mass arrests began, Lutfiye responded by writing and documenting the situation.

ATTACKS, DETAINMENTS

AND INTERROGATIONS

Russia has detained and interrogated Lutfiye three times. In 2019, during Ramadan, the Russian police took Lutfiye off the street near her home. She was detained, interrogated, and fined for her work. Lutfiye saw this as a warning of what was to come if she continued writing, a threat which she chose to ignore. “They wanted to make me scared. But it was exactly the other way around. Surviving this meant I overcame my fear.” Then, on the 22nd of February 2024, the Russian Police from the ‘Centre for Counter Extremism’, entered Lutfiye’s house at 6 am. Early morning raids on the homes of Crimean Tartars are so common that Lutfiye often sleeps in her clothes, in anticipation of arrest. The police took a video register, telephones, a laptop, flash drives, and two books. She was taken to a detention centre called the Center for Counter Extremism, a unit controlled by the Russian Interior Ministry. She was charged with ‘abuse of freedom of mass information’ for Facebook posts dating back to 2021 and later found guilty, resulting in a RUB 2000 fine. Both court decisions were upheld on appeal. On May 6, 2024, a police officer visited her for questioning at the Center for Counter Extremism’s request. The next day, another officer handed her a warning concerning the “inadmissibility of extremist activities” and “law violations during mass events” without specifying details.

MONTHY DISPATCHES

-3.png)

DETAINED DURING RAMADAN

MARCH 2025

It was back in 2019 and Ramadan had already started. I had invited members of the Crimean solidarity movement to visit for an Iftar dinner. So I was shopping, carrying bags with food when two cars stopped next to me. Unknown men with balaclavas ran out and surrounded me. The men told me I was being arrested. I asked them to give me a few minutes as my children were home alone and I had many shopping bags but they said no. I was really scared for my safety. I managed to tell my husband that I was being arrested. He rushed to me but I was already in the police car and he couldn’t do anything. As we drove away, he followed in his car. This is a good thing to do, as there are cases where people disappear completely after being arrested. I thought they would take me to the local police station but they drove for two hours to the Centre for Counter Extremism. I was detained and surrounded by these men who I didn't know and for sure, these people had previously tortured journalists. They wanted to start a dialogue with me, but I remained silent. I didn't trust them; the more I said, the more they could gather information against me. I was detained and surrounded by these men who I didn't know and for sure, these people had previously tortured journalists. They wanted to start a dialogue with me, but I remained silent. I didn't trust them; the more I said, the more they could gather information against me. I also knew that many of them were traitors - that they were previously working for the Ukrainian Secret Service and then they betrayed their own and started working for the Russians. After seven hours, I was released. The next day, there was a court hearing against me, and the court decided I was guilty. I was not surprised at all because the courts were operating with the police and the security forces. Fortunately, this was only an administrative case, so I was not imprisoned but had to pay a small sum of 2000 rubles. This is a scheme that the court has where they start administrative cases as a way to show activists that they are being watched and to make them stop. But it was exactly the other way around. I had been detained and surrounded by men who I didn't know, which had always been my deepest fear. Surviving this meant I overcame my fear.

THE REPRESSION MACHINE

APRIL 2025

The human rights movement Crimean Solidarity was created on 9th April 2016 as an informal and peaceful human rights organisation to protect victims of repression on ethnic, religious and political grounds in Crimea. Its foundation originated from the Crimean Tatar community. Groups of lawyers work to protect the Crimeans, providing initial legal consultations for members of the so-called risk group - civic activists, journalists, bloggers, and representatives of religious organisations. Today, more than 224 Crimeans are political prisoners, and countless others have fled. Crimean Tatars make up more than two-thirds of these prisoners - 133 people. The total prison term for those who have been convicted (excluding those who have already been released) amounts to 1709 years of imprisonment - according to the list of political prisoners provided by the Representative Office of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. Through my research and conversations with victims, I’ve come to realise that many of these cases are fabricated and that people are being unjustly imprisoned. The majority of political prisoners - at least 170 people - have been illegally transferred from Crimea to penal colonies and pre-trial detention centres in the Russian Federation The most recent example is 64-year-old Servet Gaziev, who has been transferred 12,000 kilometres from Crimea to Kamchatka. A third of political prisoners have now died in a Russian prison. 70 people out of 224 need medical care - these are people with disabilities, the elderly, those who have chronic diseases, or who have acquired new diseases while in prison. 6 people have disabilities, these include Amet Suleymanov, who needs an urgent heart surgery, as well as Oleksandr Sizikov who is completely blind, and has been sentenced to 17 years. Being a woman used to be a red line - one that Russian law enforcement rarely crossed. That changed after February 2022 and the start of the full-scale invasion. Since then, at least 23 women (from Crimea and those transferred there from Herson or Genichesk after 2022) have been detained. Of these, only 6 have received sentences - including Iryna Danylovych and Iryna Horobtsova. The others remain in pre-trial detention centers in Crimea or in the Russian Federation. I also want to speak about the repression of entire Crimean Tatar families who have been subjected to persecution. A striking example is the Omerov family, in which all the men - father Enver Omerov, son Riza Omerov, and son-in-law Rustem Ismailov - were arrested on trumped-up terrorism charges. The daughter and daughter-in-law were also targeted in administrative cases. Recently, even Riza Omerov’s father-in-law was subjected to a search. Three sons of Crimean Tatar historian Shukri Seytumerov and his wife, schoolteacher Lilya Seytumerova, were arrested: Seytumer, Osman, and Abdulmejit. The Russian FSB detained them, accusing them of terrorism and anti-constitutional activities. The court sentenced Seytumer to 17 years in prison and Osman to 14 years. Abdulmejit is still under investigation. The mere act of attending a mosque made them suspects. “Crimean mosques have once again become places of fear, where the Russian FSB is searching for new victims,” their father tells me. But the most vulnerable and unprotected victims of this powerful and unpunished repressive machine are the loved ones of political prisoners - their parents, wifes, and children. According to the Crimean Childhood project, which supports children of political prisoners, 252 children are currently growing up without their fathers. Many of them required psychological rehabilitation following house raids. The Russian authorities steal years of their lives, depriving them of the simplest and most precious moments of daily life: shared breakfasts and dinners, conversations about their day, smiles, hugs, and phone calls.

THE FOREIGN AGENT LAW

MAY 2025

This month, Russia escalated its campaign against Lutfiye by adding her to the list of those it falsely labels as ‘foreign agents’. First enacted in 2012 in response to protests against Vladimir Putin, Russia’s ‘foreign agent’ law requires any person or organisation receiving any form of support from outside the country to register as a ‘foreign agent’. Since Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014, the law has been enforced there as well, used alongside other repressive measures to censor and persecute Crimean Tatars. “Branding people with labels - “foreign agent”, “extremist”, “terrorist” - is quite in the spirit of our time, when laws turn into instruments of political repression. Nothing new and, alas, nothing unexpected. I still think that fighting for justice is almost always about going against the tide. It's not about accepting imposed rules or someone else's agenda. It's about making a choice once and staying true to it.” - Lutfiye Zudiyeva The law has been progressively expanded through numerous amendments, and in 2019, Vladimir Putin signed legislation that allowed the targeting of media outlets and for the authorities to label almost any journalist, blogger, or writer a ‘foreign agent’. Individuals and organisations targeted under the law face severe restrictions on their activities and risk large fines or criminal prosecution for not complying. “They are trying to make me look like a ‘leader of foreign influence’, but I write journalistic texts and defend people's rights in a very conscious and deliberate way. This is my adult choice because Crimea is my home. Recognition as a foreign agent helps to limit the activities of such people, in addition to everything — it is an attempt to discredit journalists and human rights defenders in the eyes of society. In fact, this is a discriminatory status.” - Lutfiye Zudiyeva The classification results in intensive administrative burdens, including mandatory audits, detailed reporting requirements, and being forced to label all publications with a disclaimer indicating ‘foreign agent’ status. The label also restricts you from holding positions in government bodies, running in elections, carrying out educational activities with those under 18, and working in state education. “I will have to accompany every post I write with a discriminatory foreign agent note. But if I have to choose between that and silence - silence about the arbitrariness, the arrests, the searches, the trumped-up cases - I choose not to be silent. I was prepared for this scenario but I don’t plan on stopping my work” - Lutfiye Zudiyeva Lutfiye Zudieva is the first Crimean Tatar journalist to be recognized as a ‘foreign agent’ in Crimea. She plans to file a lawsuit and appeal this decision in a court in Moscow. Until that status is removed, if a journalist refuses to put such a marking, they are threatened with administrative and even criminal punishment.

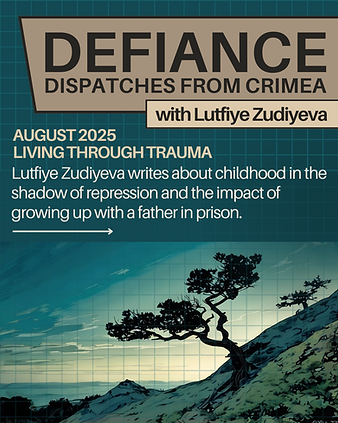

LIVING THROUGH TRAUMA

AUGUST 2025

Across occupied Crimea, many children are forced to grow up without fathers. They are the most vulnerable and unprotected victims of this powerful and unpunished repressive machine. They are the children of Crimean political prisoners. The Russian authorities steal years of their lives, depriving them of the simplest and most precious moments of daily life: shared breakfasts and dinners, conversations about their day, smiles, hugs, and phone calls. These young lives are disrupted by the brutal trauma of dawn-time raids. Each morning can feel like living through a horror film: masked, armed men bursting into homes, entering nurseries and bedrooms. These forced intrusions often leave lasting psychological effects on children, which can persist long after the events themselves. One poignant example is the story of Abdullah. After his father Ayder Djapparov was arrested, the eight-year-old turned to wrestling, declaring: “I want to be strong.” A year later, his mother Margarita, noticed a rough spot on his arm. The coach dismissed it as friction from training. But the patch grew, a silent symptom of deeper stress. Meanwhile, Margarita struggled to juggle court hearings and the demands of raising eight children. Abdullah’s health declined: stomach pain, nausea, and vomiting.A doctor quickly suggested trauma or severe stress. Within ten days, a devastating diagnosis followed: aggressive colon cancer, exceedingly rare in children. Abdullah was treated in a Turkish hospital. Activists in Crimea helped them arrange the treatment. Despite his pain, he focused on cheering his mother’s spirits, quietly more concerned for others than himself. He accepted his illness with humility, as if shouldering a burden that was not fully his own. “I only wish I could have given him what he missed most: his father's affection, his strength,” Margarita tearfully recounts. Her family was caught between her husband behind bars and a child fighting for his life. Abdullah eventually succumbed in February 2023. According to the Crimean Childhood project, which supports children of political prisoners, 252 children are currently growing up without their fathers.

FURTHER READING

CRIMEA 5AM

Created by artists in Ukraine

Read and share testimonies of those taken and imprisoned